This page explains blowing technique, fingering, and positioning Persian scales (modes) on the ney. I also provide some notes for the skeleton form of the Persian radif. These are intended as excercises for beginners so you can combine learning techique with some music. I give the "daramad" (opening theme if you like) of all 12 dastgahs plus one major gushe which is sometimes played alone. You can play them in bam and in zir; they do not use the 3d register at all.

Here are some mp3's of the excercises which I played on a B ney:

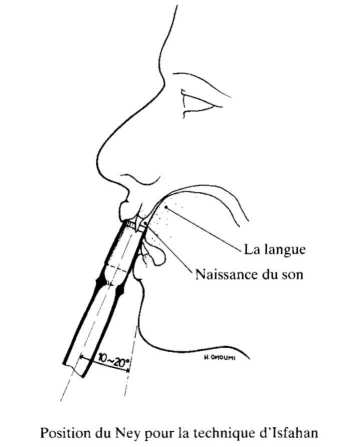

I'll try to explain how you make a sound, which is very difficult using text only. The drawing is taken from the cover of a CD by Hossein Omoumi and may clarify things.

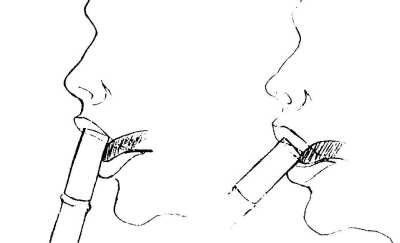

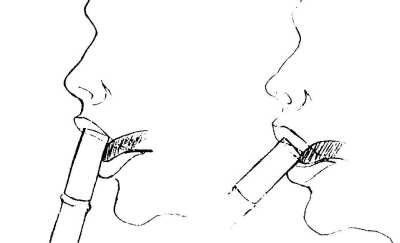

You put the mouthpiece against the cleft between your upper front teeth (or in between if you have space). About half in, half out of your mouth. Here's a bottom view:

_____(this side wedged in cleft)

|

_

---(_)-- <--(upper teeth)

| |____(this side not touching teeth, but close)

|________(blow on this edge)

Frontal view:

____(touching)

| __(not touching)

| |

|_|_|_|_| <---(upper teeth)

| |

| |

| |

|n|

|e|

|y|

|_|

The ney should be rotated slightly clockwise (1 degree maybe), so that

the upper right part is free from the teeth (this is not important

really).Your upper lip lies over the end of the ney. Touch the cleft between your lower front teeth with the tip of your tongue,

_ _ | | | <--(central lower teeth) | X | ~~~~~~~ <---(gums)where marked with X. Now touch the roof of your mouth with your tongue, but keep the tip at the location given above. With your tongue, pressed against the roof of your mouth, make a little tube, through which you blow air on the edge indicated above, blowing in the ney. Don't cover the ney completely with your lip, because the air you blow in has to bounce out partly to make a sound.

Making this tube is difficult. It feels like "hissing" with the middle of you tongue. Mussavi plays like this.

There is an alternative technique. It is as above, but you touch the rim of the ney, in the mouth, as close as possible to the teeth. Now direct the air with the tip of the tongue. This produces a softer sound. Kassai plays like this.

|

As the air is blown through a tube made between the tongue and the roof of the mouth, the natural structure of your mouth is very important. If the roof of your mouth has ridges (called rugae), you will never get a clean sound. It is speculated that the few professional players who obtain a clear sound have a naturally smooth mouth.

|

|

For myself, I use an artificial palate, molded by a dental technician, specifically to make my palate smooth. The results are excellent. Experts tell me that the quality of my tone is extremely good. (Of course, there is more to playing the ney than just being able to play one nice tone, but it is a beginning.) You can see what it looks like here.

The dental technician who has invented this device some years ago plays the ney himself. With this device, playing the ney becomes less hard. It is still a very difficult instrument, but at least it is no longer reserved for the lucky few that have no rugae on their palate.

Here is a short video which shows how to position the ney in the mouth. Look at it frame by frame, as it goes by too fast otherwise.

The precise tuning of these microtones is somewhat free. In my experience the values (40 cent for koron) given in in Dariush Talai's book "Traditional Persian art Music" (still in print) are representative of current practice in Persian traditional music. Jean During's "The radif of Mirza Abdollah" (not sure if still in print) contains interesting data on the tuning of these notes as measured from a large group of Persian masters.

Apart from these "explicit" microtones, the note immediately following the koron or sori is flat by about 20 cents (except in mokhalef-segah). this is considered part of the tuning, and not explicitly notated.

Notation: 'b' = 'flat', '#' = 'sharp', 'p' = 'koron' (60 cent flat), '>' = 'sori' (40 cent sharp).

I indicate the registers of ney by the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 with 1 the lowest producing the fundamental, the others overblowing. 1 is called "bam". There are two manners of playing bam, the strong rough bam with lots of turbulence, and the soft, smooth bam. Register 2 plays an octave higher and is called "zir". Register 3 plays an octave and a fifth higher and is called "geesh". Register 4 plays two octaves above bam and is used rarely, and is called "pas-geesh". I have never heard anyone use register 5. It is there, however (at least for good larger neys), but it does not produce any new notes and plays two octaves and a major third above bam.

The natural notes on the ney, which are played by closing all holes, and then lifting them one at a time, starting from the bottom, are as follows (click to get an audio sample). Note that the bottom note is conventionally called "C" but except on a G-kuk ney may acctually be a different pitch. In the sound samples below I play an F-kuk ney.

1: C D Ep F F# G A

2: C D Ep F F# G A

3: G A Bp C C# D E

4: C D Ep F F#

5: E F#

Note that these notes are never played in order in Persian music. Either the F is used, or the F#. With pitch-bending you can make Ep -> E in 1-2 and Bp -> B in 3. Eb in 1-2 and Bb in 3 are played by 1/2 covering the second hole from the bottom. Ap in 1-2 is played by pitch-bending and/or 1/2 covering the thumb hole. In 3 it is played by 1/2 covering the bottom hole. F> in 1-2 is played as F# with pitch-bending. 4 is only used for the high F (or F# I have heard once in chahargah).

In 1, the low B and high Bb are occasionally played by pitch-bending. Here is an example of bending the bottom note of the ney down a semitone with the lip and tongue. Here is an example of bending the top note of the bam up a semitone with the lip and tongue.

Vibrato is produced in two manners. First one can modulate the pitch of a tone by shaking the lip, listen here. Second one can modulate the loudness by oscillating the airpressure, listen here. In practice the most pleasant vibrato is a combination of the two, listen here.

The left hand generally covers the top four holes, the right hand the lower two with index finger and ring finger. Right middle finger and thumb hold the ney in place. Of course, one can reverse left-right.

| Register | 1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

| Left thumb | O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

D |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

D |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

D |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

|||||||||

| Left index | O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

|||||||||||||||

| Left middle | O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

||||||||

| Left ring | O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

. |

. |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

O |

O |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

O |

. |

. |

. |

||||

| Right index | O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

D |

O |

O |

O |

O |

O |

D |

O |

O |

O |

O |

D |

O |

O |

O |

O |

D |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Right ring | O |

O |

D |

D |

O |

O |

D |

D |

O |

D |

D |

O |

D |

D |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Note | B | C | C# | Dp | D | Eb | Ep | E | F | F> | F# | G | Ab | Ap | A | Bb | B | C | C# | Dp | D | Eb | Ep | E | F | F> | F# | G | G | Ab | Ab | Ap | Ap | A | A | Bb | Bb | Bp | B | C | C | C# | C# | Dp | Dp | D | D | Eb | Eb | Ep | Ep | E | E | F | F | F> | F# |

The table provides a fingering chart for the ney. Closed holes are indicated by "O", half-open holes by "D". A dot "." indicates a hole that is closed for supporting the ney; depending on the mode either the left middle finger remains on, or the left ring finger remains on for support. The notes are in ascending order starting around middle C.

Each dastgah can be played in a number of positions on a given ney, which are sometimes called "rast-kuk" and "chap-kuk", indicating the normal and the alternative position. Some dastgahs can be played in more than 3 positions, but the more exotic positions are for specialized used, e.g., for a specific gushe (modal piece). The position is characterized by the "finalis", which acts as the tonic for a given mode. It is roughly equivalent to the western concept of "key".

In the tables below I indicate the positions for all dastgah by placing the notes of the scale on the registers of the ney (indicated by numbers). The first two are common positions, the others more unusual. Some dastgahs have variable notes, in which case the accidental is placed in parenthesis below.

1/2: C D Ep F G A(p)

3: G A(p) Bb C D Eb

Second position (finalis = A):

1/2: C D E(p) F G A

3: G A Bp C D E(p)

Third position (finalis = G):

1/2: C D(p) Eb F G Ap

3: G Ap Bb C D(p) Eb

1/2: C D Ep F G Ap

3: G Ap Bb(p) C D Eb

Second position (finalis = Bp):

1/2: C D Ep F(>) G A

3: G A Bp C D Ep

The F> in mokhalef-segah (a major gushe) is fingered as an F#.

1/2: C# D Ep F# G A

3: G A Bp C# D Ep

Second position (finalis = G):

1/2: C# D Ep F# G Ap

3: G Ap B C D Ep

1/2: C D Ep F# G A

3: G A Bb C D Eb

Second position (finalis Homayoun = G, Esfahan = C):

1/2: C D Eb F G Ap

3: G Ap B C D Eb

Third position (finalis Homayoun = A, Esfahan = D):

1/2: C# D E F G A

3: G A Bp C# D E

1/2: C D E F G A

3: G A B C D E

Second position (finalis F):

1/2: C D E F G A

3: G A Bb C D E

Third position (finalis G):

1/2: C D E F# G A

3: G A B C D E

Fourth position (finalis D):

1/2: C# D E F# G A

3: G A B C# D E

When you've mastered all this you are ready to jam with Shajarian!